My artworks focus on the visual archive. My intention for the work is to convey my holistic experience of being a student at Oxford University but also being a child of an immigrant mother. What does it mean for my mother to have migrated to the UK from Nigeria? What histories are entangled with this movement?

Narrating these identities and stories which have been overlooked for so long, will mean making space for the diaspora, and listening to what we have to say. Many of us are trying to reconnect knowledge frayed by time and migration. My practice has become the means to do this.

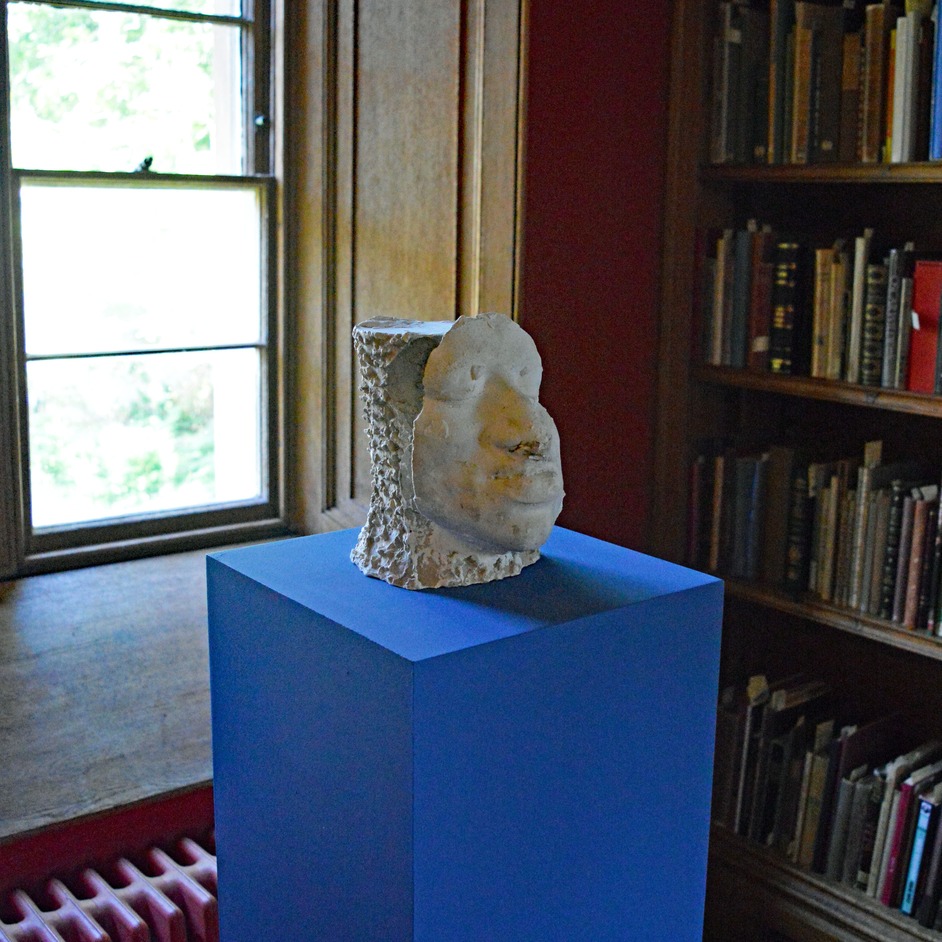

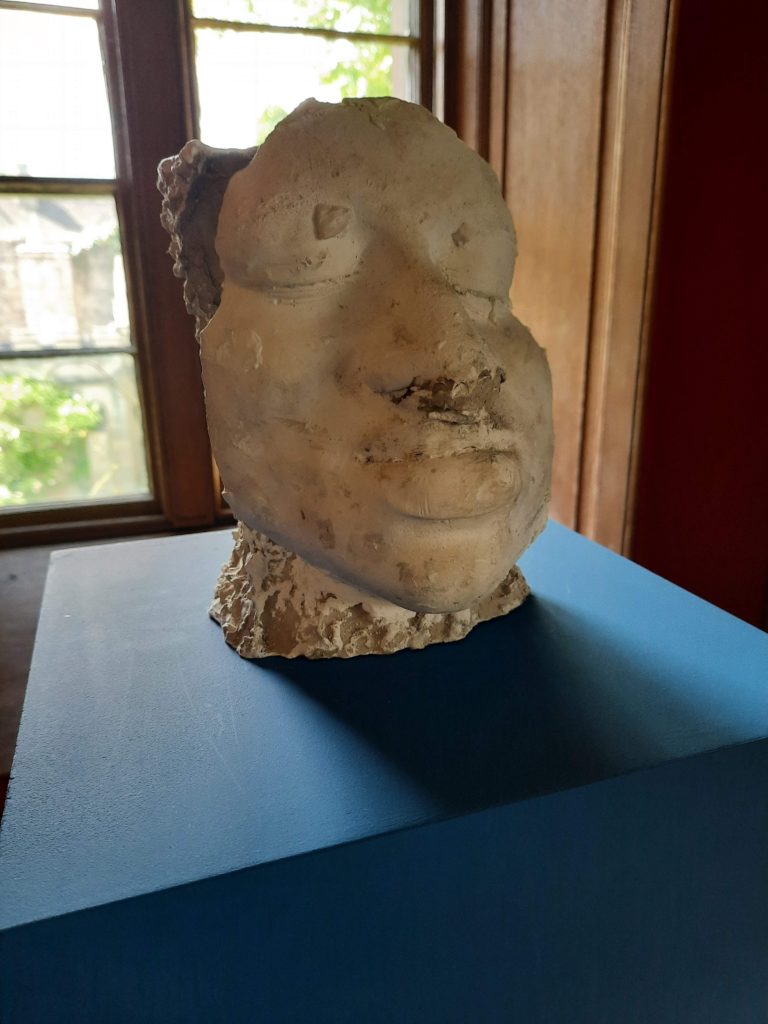

For this exhibition, I created two sculptures, ‘Rest’ and ‘Rebirth’, using plaster, oil paint, and spray paint. The sculptures became a relationship between myself and the material; the engagement of touch and sensuality that I experienced through the process of casting, carving, and moulding.

I am drawn to sculpture in the context of spirituality and ritualistic belief. I explored Yoruba spirituality, religion, and the significance of sculpture in Nigeria: intention, purpose, ritual, politics, and transformation.

It is important to consider the ethics, belonging, and politics of objects. Who should be in the presence of these objects? There is pressure on European museums and institutions, including Oxford University, to return the Benin Bronzes. Seeing these sacred artefacts in the British Museum, I feel the spiritual and physical exploitation of my Nigerian ancestors, when each of the 950 Benin Bronzes were placed in sealed boxes in the British Museum. The people of Benin should have these historical objects, to tell the stories of 400 years, embodied in these objects.

I also created a collaged fabric tapestry, ‘In the blue, we rest’, which functions as a sculpture or installation. I was thinking about finding continuities/ruptures and the work is an amalgamation of dyed fabrics and Nigerian traditional fabrics called Ankara. The margins are held together by safety pins, which can be detached, making the work adaptable and fluid.

Water is a major concept in the piece, the water represents harmony, expansion and tranquillity. Water does not fight or overpower its surroundings. Instead, it fills the cup and takes its shape, and is content with its nature or governance.

I think the freedom and possibility that water gives us is liberating, but very unsettling. Kara Walker’s monument ‘Fons Americanus’ (2019), exhibited in Tate Modern, reveals the power and the destruction that comes with water and its complacent cooperation with humanity. The curator, Clara Kim, states that the weeping boy in Walker’s fountain monument ‘resurfaces from the watery depths to call into question what we forget, as the tragic counterpart to heroic images of discovery and conquest’.[25] In my work, I am using blue as a substitute for the ocean to respond to violent pasts.

The blue also comes from Yoruba culture and spirituality, in particular Adire, an indigo dyed cloth made in Nigeria by Yoruba women. These indigenous Nigerian histories of religion and spirituality have been ruptured by colonisation, but it is important to reconnect these discontinuities, exposing the other side of the story. The deeply intertwined histories of the Atlantic Ocean connects us all and reminds us of the atrocities committed in the blue.

Paul Majek, current Magdalen undergraduate and artist